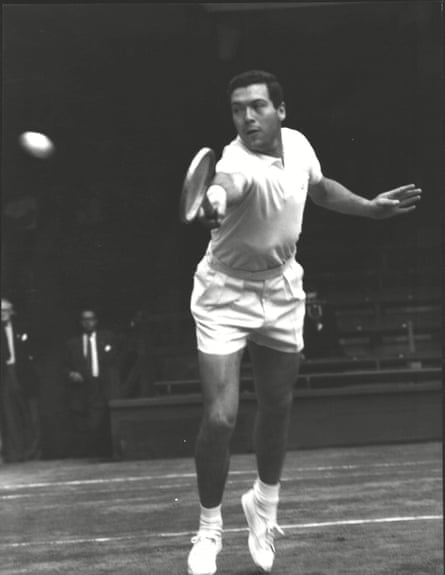

The Italian tennis player Nicola Pietrangeli, who has died aged 92, played more Davis Cup matches than anyone in the history of a competition that stretches back to 1900. In the days when the leading tennis nations played more Davis Cup ties each year than they do under the current system, Pietrangeli played 66 ties in 18 years, emerging with a proud record of having won 120 rubbers and lost only 44. Seventy-eight of those victories came in singles and he was assisted in his 42 doubles wins by his regular partner, Orlando Sirola.

Even in the current era of exceptional Italian success in tennis, led by the reigning Wimbledon champion Jannik Sinner, Pietrangeli will be remembered as one of his country’s most elegant and admired sportsmen.

His game was based on court craft and one of the most beautiful and effective backhands the game has ever seen. Most of his success came on European clay courts, but he was good enough on grass to reach the Wimbledon semi-final in 1960 when, having beaten the No 2 seed, Barry MacKay of the US, in the quarter-final, he lost to Rod Laver 6-4 in the fifth set after leading by two sets to one.

Three weeks before, Pietrangeli had established himself as the master of clay, having retained the French title he won the previous year with a five-set win over one of the best South Americans of that era, Luis Ayala of Chile. It was, however, the manner in which he lost his French crown in 1961 that lingers in the memory. Pietrangeli found himself facing a young Spaniard called Manuel Santana, whose father had been a groundskeeper at a club in Madrid.

It turned out to be the perfect match-up – the classic Italian backhand vying for supremacy over Santana’s explosive forehand, augmented by the Spaniard’s feathery touch on the drop shot. The duel held the centre court crowd at Roland Garros in rapt attention, punctuated by bursts of wild applause as the audience reacted to the feast of great clay court tennis being laid before them.

Pietrangeli led by two sets to one, but could not prevent the younger man seizing control of the match in the latter stages with a great show of aggression and when Santana wrapped it up 4-6, 6-1, 3-6, 6-0, 6-2, the one-time ball boy fell on the shoulders of the vanquished champion in floods of tears. Suddenly Pietrangeli found himself consoling the player who had just divested him of his title.

Pietrangeli, known as Nikki to his friends, was born in Tunis, the son of Anna (nee von Yourgens) and Giulio Pietrangeli. When his family moved to Rome, Pietrangeli started to play much of his tennis at one of the city’s leading clubs, the Circolo Canottieri. Quickly establishing himself as a top junior, Pietrangeli soon became an integral part of Italy’s Davis Cup team in the mid-1950s and, as players such as Fausto Gardini and Beppe Merlo began to wind down their careers, this languid, almost stately performer became Italy’s new sporting heartthrob.

Pietrangeli’s partnership with the 6ft 6in Sirola meant that Italy were frequently able to claim the all-important doubles point, and the potency of this combination enabled Pietrangeli to lead his country to its first ever Davis Cup final in 1960. They repeated the feat a year later but, unfortunately for all nations whose natural surface was clay, the Davis Cup challenge round, as it was then called, was almost always played on grass, for the simple reason that the defending nation did not have to play through. So Australia, with Laver and Roy Emerson in their ranks, had a huge advantage at White City stadium, Sydney, in 1960 and at Kooyong in Melbourne 12 months later. The Italians failed to win a live rubber in either final.

The challenge round system had allowed Australia and the US to pass the Cup between them ever since 1937. Incredibly, these two nations enjoyed a lock-out from that date until the challenge round was abolished in 1972 and, even then, the US clung on to the Cup for two more years until the stranglehold was broken when India refused to play South Africa in the 1974 final because of apartheid.

But Pietrangeli was not finished with his favourite competition. Appointed Italy’s team captain in the mid-70s, he finally achieved his goal when he ushered Adriano Panatta, Corrado Barazzutti and Paolo Bertolucci through to the final in 1976. Once again, Italy found themselves having to play the final on the other side of the world, but this time it did not matter because their opponents were Chile, the surface was clay and they won 4-1. Panatta was the new hero but the reflected glory shone rightfully on Pietrangeli, too.

Never a man to shy away from controversy, Pietrangeli was a central figure in the late 60s when the battle for control of the game was raging between the growing professional ranks and the old amateur establishment. Britain was leading the fight to throw tennis open to professionals – which eventually happened in 1968 – but, just prior to that, the reactionary Italian federation president, Giorgio de Stefani, himself a former Italian No 1, had threatened to have Britain thrown out of the international federation for fostering “illegal” plans to admit professionals to the mainstream game.

Pietrangeli had been telling me things in private conversations, and when I phoned him up in 1967 to ask him to put the salient facts on record, he did, admitting that De Stefani, in the name of the Italian federation, had paid him to stay amateur. “Yes, they paid me money,” Pietrangeli admitted, thus exposing the level of hypocrisy and “shamateurism” that was rife in the amateur game at the time. Pietrangeli’s revelation only helped to hasten the collapse of the old order.

Pietrangeli, multilingual, witty and charming, continued to be a major figure in European tennis, and was involved in the running of the Italian Open at various times. In 2006, one of the stadium courts at the Foro Italico sports complex in Rome, marble-tiered and surrounded by giant statues, was renamed the Stadio Nicola Pietrangeli in his honour.

In 1960 he married Susanna Artero, a model, with whom he had three sons, and after their divorce in the mid-70s subsequently had a seven-year relationship with the TV presenter Licia Colò. He is survived by two sons, Marco and Filippo; the third, Giorgio, died earlier this year.

2 days ago

4

2 days ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·